Python Foundations, Session 4: Object Oriented Programming¶

Instructor: Wesley Beckner

Contact: wesleybeckner@gmail.com

Recording: Video (41 min)

Today we'll be discussing a very important concept through all of programming: how to be object-oriented.

4.1: Object Oriented Programming¶

4.1.1 Classes, Instances, Methods, and Attribtues¶

A class is created with the reserved word class

A class can have attributes. You can think of these as charateristics that describe the object.

# define a class

class MyClass:

some_attribute = 5

Defining a class in the above way, creates a blueprint. We use the class blueprint MyClass to create an instance. And after we do so, we can now access attributes belonging to that class:

# create instance

instance = MyClass()

# access attributes of the instance of MyClass

instance.some_attribute

5

attributes can be changed:

instance.some_attribute = 50

instance.some_attribute

50

In practice we always use the __init__() function, which is executed when the class is being initiated. This is the pythonic way to be explicit about initializing the attributes of our class

Upon investigation, you will find that the trouble with not using the

__init__()method is that your attributes are not guaranteed to be initialized upon creation of the object from the class blueprint

# define a class

class MyClass:

# we define our __init__ method that is called when the object is initialized

def __init__(self): # we pass in the reserved word self

# we reference the current object of the class via the self parameter

# and set its attributes

self.some_attribute = 5

When we use __init__, we also have to make use of a special reserved word in python: self. The self parameter refers to the current instance of the class. In other words, when the object is declared, it will refer to that specific object in memory and not all instances of the class in question. This is yet another pythonic way of being explicit.

what is the special keyword

selfdoing, do we really need it? Read more about the philosophy of the self by visiting the link!

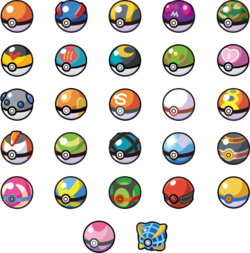

Let's practice class declaration now, in the context of Pokeballs

We have a lot of different kinds of Poke balls! This is going to help us understand some of the powerful mechanisms inherit in python classes!

Let's start by defining a class to describe the simple, standard Poke ball. It will have the following attributes:

containsthe name of the pokemon contained in the Poke ball. Default value isNonetype_namethe type of Poke ball. Default value is"Poke ball"catch_ratethe probability of a successful catch upon throwing the Poke ball. The default value is0.5and the user will not be able to set the value of this object.

Let's take a look at how we do this:

# define the class in the standard way via the reserved word class

class Pokeball:

# define the init method pass in the "self" and any attributes that will

# be definable upon initialization of the object

def __init__(self, contains=None, type_name="Poke ball"):

# now set the attributes of the object via the self

self.contains = contains

self.type_name = type_name

self.catch_rate = 0.50 # note this attribute is not accessible upon init

# empty Poke ball

pokeball1 = Pokeball()

# used Poke ball of a different type

pokeball1 = Pokeball("Pikachu", "Master ball")

🙋 Question 1: What are the parameters of Pokeball?¶

Note that, were we to run the following cell, we would get an error. Why would we get an error?

# Pokeball("Charmander", "Poke ball", catch_rate=0.5)

classes can also contain methods. I'm going to introduce a new method catch that is used to catch new pokemon. It will have a random chance of success and, additionally, it will only work if the Poke ball is empty.

import random

class Pokeball:

def __init__(self, contains=None, type_name="Poke ball"):

self.contains = contains

self.type_name = type_name

self.catch_rate = 0.50 # note this attribute is not accessible upon init

# the method catch, will update self.contains, if a catch is successful

# it will also use self.catch_rate to set the performance of the catch

def catch(self, pokemon):

if self.contains == None:

if random.random() < self.catch_rate:

self.contains = pokemon

print(f"{pokemon} captured!")

else:

print(f"{pokemon} escaped!")

pass

else:

print("Poke ball is not empty!")

We can envoke the catch method the same way we would return the attribute of an object - by running <object>.method(). Note that, because this is a method, we must use (), the same way we use () with functions. Inside the () we pass any necessary parameters. In this case we will pass the name of the Pokemon we are trying to catch:

pokeball = Pokeball()

pokeball.catch("picachu")

picachu captured!

print(pokeball.contains)

picachu

🙋 Question 2: How does catch_rate work?¶

How often will success print to the output when we run the cell below?

if random.random() < 0.5: # here I've replaced catch_rate with the hardcoded value 0.5

print('success')

🏋️ Exercise 1: Write a Method¶

Create a release method for the class Pokeball:

# Cell for Exercise 1

import random

class Pokeball:

def __init__(self, contains=None, type_name="Poke ball"):

self.contains = contains

self.type_name = type_name

self.catch_rate = 0.50 # note this attribute is not accessible upon init

def catch(self, pokemon):

"""

Used to catch Pokemon with an empty Poke ball. Has a probabilistic chance of

success.

"""

if self.contains == None:

if random.random() < self.catch_rate:

self.contains = pokemon

print(f"{pokemon} captured!")

else:

print(f"{pokemon} escaped!")

pass

else:

print("Poke ball is not empty!")

def release(self):

pass

4.1.2 Inheritance¶

Inheritance allows you to adopt into a child class, the methods and attributes of a parent class. We inherit a parent class by passing it into the child class:

# Pokeball is the parent class and Masterball is the child class

class Masterball(Pokeball):

pass

Once we declare an object of the child class. We will have access to all of the parent class attributes. In this case, masterball will inherit the type_name of "Poke ball" from the Pokeball class:

masterball = Masterball()

masterball.type_name

'Poke ball'

HMMM we don't like that type name because this is not a regular-old Poke ball anymore. It is a Master ball!

Let's make sure we change some of the inherited attributes.

We'll do this again with the __init__ function

# we still pass Pokeball into Masterball

class Masterball(Pokeball):

# now we pass into the init method the class attribute values we actually

# desire, instead of just inheriting them from the parent class

def __init__(self, contains=None, type_name="Masterball", catch_rate=0.8):

self.contains = contains

self.type_name = type_name

self.catch_rate = catch_rate

masterball = Masterball()

masterball.type_name

'Masterball'

masterball.catch("charmander")

charmander captured!

We can also write this, this way:

class Masterball(Pokeball):

def __init__(self, contains=None, type_name="Masterball"):

# instead of rewriting all of the self.<attribute> commands, we can access

# the init method from the parent class (where those commands are already

# declared)

Pokeball.__init__(self, contains, type_name)

self.catch_rate = 0.8

masterball = Masterball()

masterball.type_name

'Masterball'

masterball = Masterball()

masterball.catch("charmander")

charmander captured!

The keyword super will let us write even more succintly:

class Masterball(Pokeball):

def __init__(self, contains=None, type_name="Masterball"):

# super() is taking the namespace of the parent class, note that with this

# mechanism we no longer have to pass in the self attribute

super().__init__(contains, type_name)

self.catch_rate = 0.8

masterball = Masterball()

masterball.catch("charmander")

charmander captured!

🏋️ Exercise 2: Create a Class¶

Write another class object called GreatBall that inherits the properties of Pokeball, has a catch_rate of 0.6, and type_name of Greatball

# Cell for Exercise 2

4.1.3 Interacting Objects¶

As our application becomes more complex, we may have to rethink what methods and attributes are appropriate for our objects to deliver the overall functionality we desire. This is where form and function meet.

🏋️ Exercise 3: Interacting with Objects¶

Write another class object called Pokemon. It has the attributes:

- name

- weight

- speed

- element

Now create a class object called Fastball, it inherits the properties of Pokeball but has a new condition on catch method: if pokemon.speed > 100 then there is 100% chance of catch success.

what changes do you have to make to the way we've been interacting with Poke ball to make this new requirement work?

# Cell for Exercise 3

🏋️ Exercise 4: Writing Tests¶

In the above task, did you have to write any code to test that your new classes worked?! We will talk about that more at a later time, but for now, wrap any testing that you did into a new function called test_classes in the code cell below

# Cell for Exercise 4